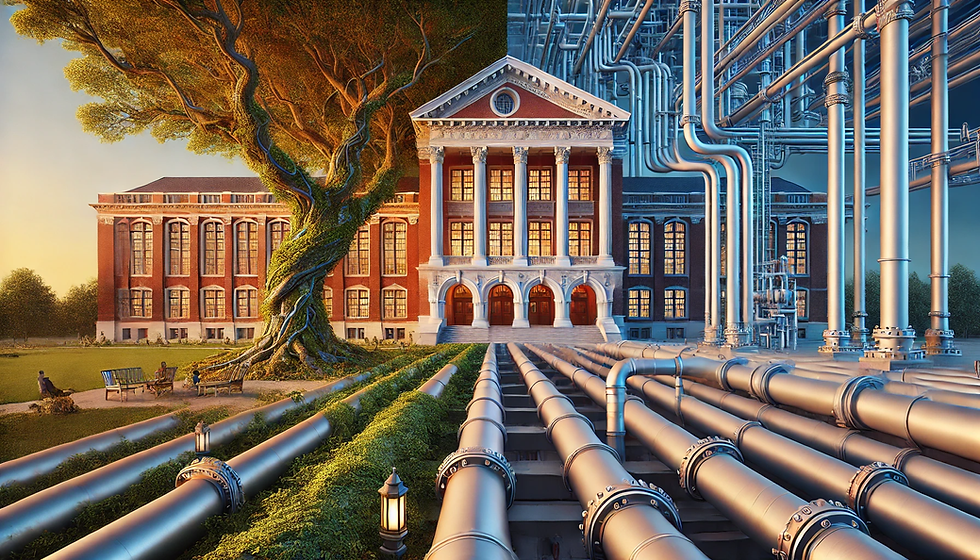

Institutions of Knowledge: Past Legacies, Present Crises, Future Forms

- Arpit Chaturvedi

- Jul 30, 2025

- 5 min read

The world over, a new elite has, in some way or the other overthrown an older elite. With it, it is attempting to overthrow its institutions too. Academics, journalists, and universities have been facing increasingly tough times either due to financial paucity or socio-political opposition. There are several ways of looking at this phenomenon. One way to look at it is that the information technology revolution, so to say, “democratized” information. “Everything you need is on Google, on ChatGPT, on Coursera…” etc. became a favorite repertoire of people often startled by technology. The truth however, is that “many things are on Google, ChatGPT, or Coursera”, but many things are not. Even now, the despite claims that “ChatGPT can answer Phd. level questions” or whatever is the favorite new social media claim akin to this is ill founded for anyone who engages deeply with the enterprise of knowledge. Yet, it is true that technology firms as an institution have made a severe dent on the institution of higher education. So far, education was a good club, you paid a university or school and received education once you were part of that club. Now, even if the quality of the best online content does not match that of the educational experience at the best of the educational institutions, technology has been able to deliver a general sense or a feeling that these institutions providing club goods are dispensable and that education is a public good.

The confusion seems to stem from a lack of clarity in the difference between data, information, knowledge and wisdom (Russell L. Ackoff, 1989). What the information technology revolution did was that it democratized information. As soon as something was on internet, it could be accessed by anyone. Then came the paywalls, another attempt to guardrail or convert onto club goods, the knowledge that one can derive out of the information available. What ChatGPT is doing, to a large extent, is that it is making knowledge available to everybody. For example, I do not understand the complex symbolic language of physics but I was able to read works of Benoit Mandlebrot, full of mathematical technicalities, by simply copy pasting the equations and symbols in various AI softwares and deriving meaning with their aid. What technology has not been able to do and for now, I suspect, that it would not be able to ever do it to replace wisdom – the last of the human bastions.

Two definitions of wisdom stand out for me. The first is by Robert Sternberg who argues that “wisdom is the application of tacit knowledge as mediated by values toward the achievement of a common good through a balance of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extrapersonal interests.”[1] Another is Marc Prensky’s who says, wisdom is the “ability to find practical, creative, contextually appropriate and emotionally satisfying solutions to complicated human problems.”[2] Technology can be a good aid for wisdom, but it will not however, be able to be the source of it. Eventually it is people who will have to make the decision, or to accept or reject decisions proposed by technology produced knowledge systems.

Nevertheless, the core of my argument is that the knowledge institutions that are producing these technologies (tech firms etc.), are waging a war against old knowledge institutions and rendering them obsolete to the extent that they are not serving their own purpose of giving extremely specialized education in technology. This was the first explanation of the crisis that the educational system faces from the lens of technology.

Another explanation of the crisis is that there is a section in every society which has been denied access to institutions of higher learning. And their thinking is that these institutions, good as they may be, have not served to further their interests (i.e., of certain sections of society) and therefore, they wouldn’t mind if these institutions were completely eradicated.

A third explanation is that the educational institutions, whatever their claims may be, have stopped playing a useful role for the society. In the name of “critical thinking” and “specialized research”, they have duped the masses and have either left them with mountains of debt or hollow promises of cutting edge research that barely solved any problems. Their “ivory towers” are mere snob clubs that have been systematically duping the society by promising them a dream that was never going to be fulfilled. Since, these institutions have outlived their utility, it is time that we say goodbye to them.

For a moment, it is useful to not be an apologist for the educational institutions. It is possible that all three lenses, the technological, the socio-political, and the institutional utility one are correct at the same time. What would be the consensus conclusion then? That the educational institutions will decay. Let us say we are ok in eradicating them or limiting them to the extent that they serve the needs of the new overlording institutions, i.e. the tech firms. What happens then? Knowledge production could get consolidated within private tech monopolies. When that knowledge production is efficiently done in-house, the tech firms will not invest in universities. However, when that knowledge production becomes costly to produce internally due to various competitive factors, and it is cheaper to outsource it, the universities will be back with a vengeance, albeit new forms of universities. Yet, how is that structure any different from what the large universities already were? They were pooled, outsourced institutions of knowledge production for ruling institutions, whether states or corporates.

When the state or dominant interests within a state did not find knowledge it feasible to impart specialized knowledge for its functionaries and elites at scale, they devised an institutional mechanism in form of the university. Oxford and Cambridge, were clerical training grounds, producing literate men for ecclesiastical, legal, and administrative roles. The trivium (grammar, logic, rhetoric) and quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music, astronomy) were the core curriculum, geared toward forming functionaries of the Church and Crown. The German universities, upon which the United States’s universities were partly modeled in addition to the influences of the British institutions, were also hailed because Humboldt and other institutions of higher learning were seen as causal to strengthening the German/Prussian state.

Harvard, founded in 1636, was the first such institution in the American colonies—created by the Puritan elite to train clergy and magistrates who would uphold the civic-theological order (or state elite administrators) of the new settlements.

The university’s role as a “refuge for inconvenient minds” only came much after when state ambitions and competition among states grew to a point where quirks of some individuals were tolerated if they gave the state a huge competitive advantage. Yet, Turing was persecuted on allegations of being homosexual, then outlawed in Britain (despite having duly served state interests). The United States later transformed the “if utility, then freedom” into a logic into the “if freedom, then utility” mantra for academics. It turns out that the mantra also served them very well.

However, that mantra has somewhat played its hand and the impulse is towards moderation and correction in the other direction. The nature of state is changing and so will the nature of higher education. The challenge therefore is to execute an institutional transformation that is smooth enough so that the best of the old institutional knowledge is preserved and there is ample room for the new metamorphosis of the university with a new type of state.

[1] Sternberg RJ. Wisdom, intelligence, and creativity synthesized. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press; 2003.

[2] Prensky M. Brain gain: technology and the quest for digital wisdom. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan; 2012.

Comments